There are so many more salient questions – what will this mean for British politics, for the post-Brexit trade negotiations, for the NHS? – but it is perhaps worth dwelling briefly on first thoughts about possible implications for UK-Russia relations.

Is the weaponization of Russia done for the moment? Russia’s role in the election campaign was solely instrumental, mobilised by both main parties to smear the other. Johnson’s decision to shelve the Intelligence & Security Committee’s report on Russian influence, of which more below, probably because of embarrassing detail about links between the Conservatives and sundry rich Russians, some of whom may have got their money through questionable means, inevitably left him open to allegations that he and his party were all but bought and paid for. In response, after generally portraying Jeremy Corbyn as soft on Russia (not without grounds: his initial response to the Salisbury attack was, in my opinion, disgraceful), the Tories were able to use the claim that Russian-linked web accounts had been used to publicise a leaked report on UK-US trade talks to suggest that he had been played by Moscow, or even somehow in cahoots with the Kremlin. The Tories and their media cheerleaders gleefully demanded he “come clean” as if the leak had not been out openly on the internet for weeks before Labour came across them.

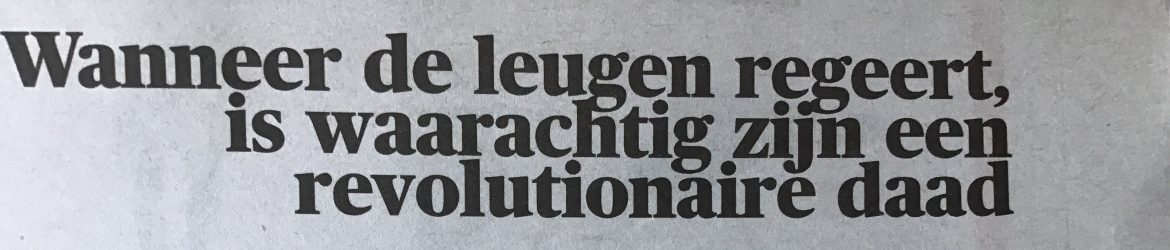

Of course it was never very likely that there would be a meaningful debate about Russia policy in the election, and it means nothing that there was not. Essentially, this was a debate kept squarely within the iron triangle of Brexit, the NHS, and leaders’ personalities. However, that supposed and darkly-speculated Russian connections were deployed so freely as smears speaks to a depressing degradation in the language of politics but also a worrying caricaturing of Russia and its role in the world. This may have just been campaign knock-about, but it risks getting in the way of subsequent proper policy debate. Russia is a challenge but it is not a mortal enemy, and the UK is a serious international player and its ambitions to be “Global Britain” should make it more, not less important that its leaders embrace and understand nuance. Washington has already succumbed to the pathology of viewing Russia almost entirely through the lens of domestic politics, and the hope must be that London can resist following.

Will Britain get soft on Russia? This is an inevitable concern, but I suspect not. Nor, though, do I think London will see any reason to adopt a stronger line on Moscow. The issue that I think will emerge is that a “swashbuckling” post-Brexit UK may well quietly roll back some of the progress in addressing the dirty money flowing into London – not just Russian – especially as the economy suffers from the inevitable dislocations. I deeply regret this, but it is hard not to assume this is a given. Of course, that facilitates the activities of all kinds of dodgy characters, from gangsters to oligarchs, money launderers to corruption brokers. However, I have seen no serious evidence that this actually has a meaningful impact on policy. We’ll see what the ISC report says when it eventually comes out, but I suspect that such influence/corruption as may exist tends to operate at a personal, not national level – individuals lobby for outcomes that help their own interests, not part of any coordinated Kremlin campaign.

So UK plc may well be soft on dirty Russian money, but not Russia itself. After all, Johnson was the foreign secretary on whose watch the coordinated post-Salisbury expulsion blitz was engineered by British diplomacy, and the UK remains a key practical backer of Ukraine. The UK strategy will remain managing and containing Kremlin mischief in the immediate term, while hoping to build more positive relations in the longer. That generally is assumed to mean post-Putin, but it would be interesting to see if Moscow has the imagination to launch a charm offensive now. (I suspect not.) Barring that, I doubt there will be any change, although it could be that a UK government feeling to need to demonstrate its international clout might try to position itself as a champion against Russian adventurism. I honestly hope not, though (unless there is some new casus belli, a second Salisbury or the like), because this would likely be driven, as noted above, by domestic considerations more than the needs of the international situation.

So will it affect European relations with Russia? Brexit will, frankly, be bad for the security of Continental Europe, especially as relates to Russia. NATO will endure (it is not so much brain dead as mildly concussed, and it will get over it), but the challenge from Moscow is not of tanks rumbling through the Suwalki Gap, but a continuing campaign of political war, of undiplomatic diplomacy, of overt pressure and covert subversion, of disinformation and discombobulation. While many countries are seeking to address this, and the EU is to an extent, this is a struggle which puts particular weight on good and tough diplomacy, on strong intelligence and security services, and on agility and a sneaky imagination – all of which are British strengths.

(Which is just as well, as Johnson’s promises of tax cuts, more money for the NHS, more police, etc, doesn’t look like it will leave much for increases to regular defence spending.)

Whatever the platitudes about “our European friends,” as the Brexit negotiations move into the detailed trade and political talks, the likelihood is that these will get tough and possibly nasty. This will inevitably have an impact on London’s willingness – and ability – to work with its European neighbours outside the NATO context on tricky security matters. I suspect this is one aspect of Brexit that Europe will come especially to regret.

Anyway, those are my first thoughts and like all hot takes will no doubt be overtaken by events. The assumption seems to be that there will be no major reshuffle, but it will be interesting to see who will occupy the positions of foreign and defence secretary. We’ll see.