Antwoord van AH, nieuwe acties bij hoofdkantoor en opnieuw in de raad!

Nieuwsbrief 32

www.behoudlutkemeer.nl | info@behoudlutkemeer.nlBekijk de webversie

Behoud Lutkemeer zet zich in om de Lutkemeerpolder te behouden voor de stad Amsterdam. Ook steunen? Deel deze nieuwsbrief en houd onze website en facebookpagina in de gaten voor activiteiten, demonstraties en oproepen.

vrijdag 25 juni 13.00 volgende actie bij AH-hoofdkantoor. Kom ook!

Eind mei hebben we gevraagd om een gesprek met de directie met AH en om een reactie op het voornemen om in de Lutkemeerpolder te gaan bouwen. Albert Heijn, trek je terug is ons devies. Naar aanleiding van hun reactie zien wij ons genoodzaakt door te gaan met acties. De eerstvolgende actie is bij het hoofdkantoor in Zaandam op vrijdag 25 juni om 13.00. (Provincialeweg 11). Een leuke fietstocht, of gezamenlijk vanaf station Zaandam, verzamelen om 12.45. We zullen de directie uitnodigen om de polder met eigen ogen te zien en laten tijdens het protest vogelgeluiden horen, van vogels die dreigen te verdwijnen. AH legt de verantwoordelijkheid bij de gemeente als ontwikkelaar, maar zonder koper, geen verkoper. Het is een zelftstandige keuze van AH om in de Lutkemeerpolder te bouwen. Heel recent opende AH nog een enorm distributiecentrum in Westpoort aan de Beiraweg 3, slechts 7 km verderop. En dat ze zeggen in de verkennende fase zitten is ook bijzonder. Uit de documentatie blijkt dat ze al sinds begin 2019 in gesprek zijn met de gemeente.

We hebben Ahold Delhaize een open brief gestuurd en zullen volgende week vrijdag opnieuw inzetten op een gesprek.

Recent opende AH nog een enorm distributiecentrum in Westpoort aan de Beiraweg, 7 km verderop.

English summary A battle over the Lutkemeerpolder, in the west of Amsterdam, has been raging for years now. The municipality wants to build an distribution centers. Neighbours and thousands of sympathisers want to keep the polder, its biological agriculture and nature. The interested company has been revealed: Ahold, the holding behind Albert Heijn, Etos, Gall&Gall, and Bol.com; Ahold merged in 2016 with Delhaize which also owns supermarkets in VS and elsewhere. This specific distribution center is very probably meant for Albert Heijn.

In a reaction on our last action AHOLD announced they are ‘scouting the spot’ and point the city council as responsible. Without buyer, no seller, so AH has is own responsibility. A follow-up action has been announced for next week Friday June 25th 1 pm, at the headquarters of Ahold in Zaandam. (Provincialeweg 11)

“We will continue until Ahold got the message; AH has to go away”.

Er wordt hard getuinierd in de polder, maar we kunnen nog veel hulp gebruiken.

Misschien wil je zelf een stukje tuin beheren of helpen met het wieden en watergeven in de gemeenschappelijke stukken. Het bouwen van voorzieningen is ook zeer welkom.Meld je via info@behoudlutkemeer.nl als je ook mee wilt doen.

Wat kun je nog meer doen? – Schrijf een berichtje op de publieke facebook Albert Heijn en stuur een bericht

– Bel met het hoofdkantoor: 088 6599111 of de klantenservice: 0800 0305

– Tag @AlbertHeijn op twitter (#ahmustgo #behoudlutkemeer)

– Chat met Albert Heijn op whatsapp

– Geef in je lokale Albert Heijn deze brief af aan de manager.

– Zoek op linkedin Ahold of Albert Heijn. Ken je iemand die daar werkt? Stuur een bericht.

– haal bovenstaande flyers op één van de afhaalpunten en deel deze uit bij Albert Heijn

– houd actie-aankondigingen in de gaten via onze website en social media.

Commissievergaderingen gemeente Na een maandenlange procedure is Stichting Behoud Lutkemeer eindelijk in het gelijk gesteld: ze zijn belanghebbend en de gemeenteraad moet beslissen over het verzoek Herziening bestemmingsplan. Op 30 juni is het geagendeerd bij de commissievergadering Ruimtelijke Ordening.

Eerder deze maand besprak de gemeenteraad op verzoek van Partij van de Dieren de reserveringsovereenkomst en een mogelijke komst van Albert Heijn naar de polder. Kijk hier de behandeling terug. (Inspraak is op 14.20 en 18.15)

Een transcriptie van de behandeling (incl commentaar) is hier terug te lezen.

Doneer voor de Lutkemeer De campagne en de juridische procedures kosten geld. Ook een steentje bijdragen? Doneer voor de Lutkemeer!

NL94 INGB 0007 2294 84 tnv Het Luchtkasteel ovv Behoud Lutkemeer

Geef je op voor alarmlijst Als er gedreigd wordt met zandwagens en acute actie nodig is: geef je op voor de alarmlijst. mail je telefoonummer naar info@behoudlutkemeer.nl

Niet alleen de Lutkemeer, ook de Sloterplas wordt bedreigd door de plannen van de gemeente. Lees hier meer erover!

Veel gestelde vragen over het verzet in de Lutkemeerpolder

YouTube

Website

Biden-Putin Geneva Summit, June 16, 2021

Respond to this post by replying above this line

rapper Eze Kay from Sierra Leone traveled to the main land of Greece

Eze Kay from greece’s mainland

Eze Kay: struggle of a child

20210415 ramadan edition samos calling

20210408 EzeKay moskeetape audio

Eze Kay reaction on first transfer of phone credit

sound of money to phone credit

interview with Eze Kay

more info at m2m

latest raps

Two things involved

If you wanna be me

We-d-best-in-the-east

Geen Albert Heijn in de Lutkemeerpolder. Doe ook mee!

Nieuwsbrief 31

www.behoudlutkemeer.nl | info@behoudlutkemeer.nlBekijk de webversie

Behoud Lutkemeer zet zich in om de Lutkemeerpolder te behouden voor de stad Amsterdam. Ook steunen? Deel deze nieuwsbrief en houd onze website en facebookpagina in de gaten voor activiteiten, demonstraties en oproepen.

We hebben de hulp nodig om zoveel mogelijk berichtjes naar Albert Heijn te krijgen! Hoe kan je dat doen? – Schrijf een berichtje op de publieke facebook Albert Heijn en stuur een persoonlijk bericht

– Bel met het hoofdkantoor: 088 6599111 of de klantenservice: 0800 0305

– Tag @AlbertHeijn op twitter (#ahmustgo #behoudlutkemeer)

– Chat met Albert Heijn op whatsapp

– Geef in je lokale Albert Heijn deze brief af aan de manager.

– Zoek op linkedin op Ahold of Albert Heijn. Ken je (via via) mensen die daar werken? Stuur ze een berichtje!

– haal flyers op één van de afhaalpunten (zie elders in de nieuwsbrief) en deel deze uit bij een Albert Heijn filiaal

– houd actie-aankondigingen in de gaten via onze website en social media.

Paar tips:

– Als je te horen krijgt dat die persoon het niet weet, laat je vraag doorsturen. De aanhouder wint.

– Als je te horen krijgt dat het nog maar een verkenning is: dit is wat de gemeente daarover zegt: “De partij waarmee de eerste reserveringsovereenkomst is gesloten d.d. 12 maart 2020 heeft aangegeven extra tempo te gaan maken in de planvorming zodat in mei 2021 het definitief ontwerp kan zijn afgerond. Vervolgens zal conform de huidige planning in juni de investeringsbeslissing worden genomen, de omgevingsvergunning aangevraagd en naar buiten worden gecommuniceerd over de ontwikkeling.”

Omslagpunt Lutkemeerpolder. Naam multinational bekend: Ahold! Eindelijk is de naam bekend van het concern dat een distributiecentrum zou willen vestigen in de Lutkemeerpolder. Hoewel het bedrijf en de gemeente dat geheim wilden houden (om de tegenstanders geen kans te geven om zich te verzetten) hebben we de infromatie uit hun eigen stukken.

Het betreft AHOLD, het concern dat eigenaar is van Albert Heijn, Etos, Gall & Gall en Bol.com en sinds 2016 met Delhaize is gefuseerd, die ook supermarktketens in de VS en elders bezit. Maar waarschijnlijk gaat het distributiecentrum vooral de winkels van Albert Heijn bedienen.

Ahold zou een reserveringsovereenkomst hebben getekend voor een stuk van 5,5 ha in de Lutkemeerpolder, om daar een distributiecentrum te bouwen. Dit blijkt uit documenten die via een WOB-procedure losgekregen werden. De naam van het concern was weggelakt, maar op één plek in de reserveringsovereenkomst waren ze dat vergeten.

De Amsterdamse gemeenteraad had geëist dat er daadwerkelijk een koper zou zijn, voordat er met bouwwerkzaamheden zou worden begonnen. Dit om te voorkomen dat er een industrieterrein zou worden aangelegd waarvan een groot deel van de kavels leeg zou blijven staan, zoals in het aanpalende 1e bedrijvenpark Lutkemeer.

Keer op keer werd er door de gemeente beweerd dat het nu toch echt rond was:

– in 2018 oordeelde de rechter dat biologische boerderij De Boterbloem moest vertrekken, omdat de gemeente aanvoerde in gesprek te zijn met een bedrijf dat spoedig zou leiden tot een overeenkomst

– in 2019 moesten de Tuinen van Lutkemeer worden ontruimd want, zo bepaalde de rechter: ‘volgens de gemeente gaat er in september gestart worden met werkzaamheden en is de overeenkomst zo goed als rond.

– in 2020 berichtte de wethouder dat er een reserveringsovereenkomst was getekend met een ‘geheim’ bedrijf.

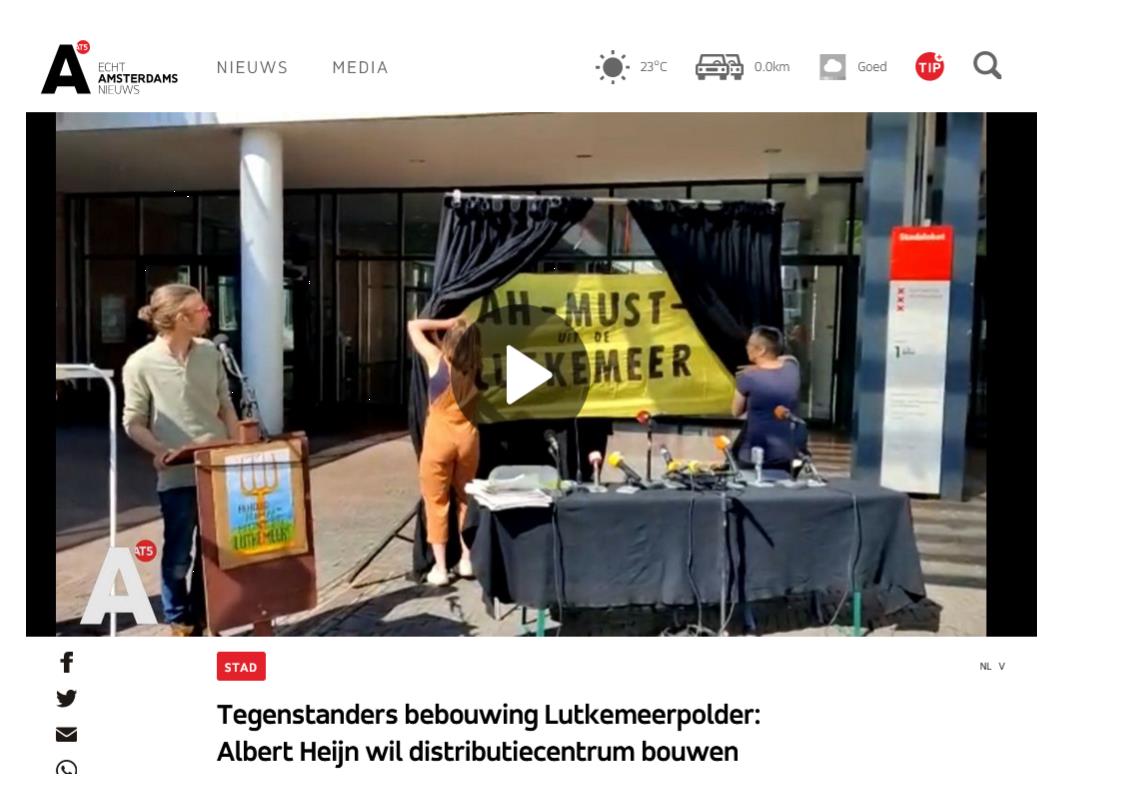

– in 2021 bericht diezelfde wethouder dat het tekenen van een daadwerkelijke overeenkomst is uitgesteld naar juli 2021Maar Albert Hein zelf zegt ‘in een verkennende fase te zijn’, toen de lokale Amsterdamse zender AT5 Albert Heijn om een reactie vroeg. “er wordt nog gekeken of er daadwerkelijk gebouwd gaat worden, Albert Heijn onderzoekt de mogelijkheden om daar een logistiek punt te plaatsen”

Dit is volledig in tegenspraak met de uitspraken van wethouder Van Doorninck en haar ambtenaren, die al bijna vier jaar beweren dat er echt een koper is en dat er elk moment een definitieve koopacte gesloten zal worden.

Na de bekendmaking afgelopen vrijdagmiddag bij de Stopera zijn meteen met ruim honderd mensen met veel lawaai naar de meest dichtstbijzijnde vestiging van Albert Heijn getrokken. Daar is een korte symbolische blokkade uitgevoerd, om duidelijk te maken wat het concern te wachten staat als de plannen doorzetten. “We gaan overal actie voeren en eisen dat ze met hun handen van de Lutkemeerpolder afblijven” verklaarden actievoerders daar voor de deur. “Ahold heeft nu de kans om te laten zien dat ze echt hart heeft voor de kleintjes, en voor het klimaat. Biologische aardappelen komen daar uit de grond, niet uit een vliegtuig op Schiphol.” Flyers (zie foto) doken al snel ook in andere Albert Heijn-vestigingen in Amsterdam op, evenals in Haarlem en Utrecht.

Er zijn voor komende weken al meerdere acties aangekondigd, bij vestigingen op diverse plekken in de stad en elders in het land, en bij het hoofdkantoor in Zaandam. “We gaan daarmee door tot de boodschap bij Ahold aangekomen is; AH has to Go uit de Lutkemeerpolder”.

Verschillende (online) media en platforms maken melding van de actie, zoals dit vastgoedblad, een blog van de lector City Logistics en de nieuwsbrief van Warehouse Totaal. Daarnaast is het door lokale media opgepakt.

Er wordt hard gewerkt aan de tuinen, iedere zondag is iedereen welkom om mee te helpen. Komend weekend is een onderdeel van het Food Autonomy Festival in de Lutkemeer. Meer hierover kun je hier lezen.

English summary A battle over the Lutkemeerpolder, in the west of Amsterdam, has been raging for years now. The municipality wants to build an distribution centers. Neighbours and thousands of sympathisers want to keep the polder, its biological agriculture and nature. This week the name of the interested company has been revealed, a name which the responsible GroenLinks-alderman has been trying to keep secret for the last year. It turns out to be Ahold, the holding behind Albert Heijn, Etos, Gall&Gall, and Bol.com; Ahold merged in 2016 with Delhaize which also owns supermarkets in VS and elsewhere. This specific distribution center is very probably meant for Albert Heijn.

Ahold would have signed the reservation agreement for a plot of 5.5 ha in the polder, to build a distribution center. This got out via a public access request in which the name of the company was lacquered everywhere, except for two paragraphs.

The council of Amsterdam had demanded that there would be an actual buyer, before the building would start. This to prevent (another) fallow plot, as for example in the adjacent industrial area Lutkemeer I. The municipality and the consortium SADC, claimed in court in 2019 that “an agreement would be a matter of months” and the area, which by then were communal gardens and agriculture, had to be vacated. Last February (2021), Marieke van Doorninck announced that signing that agreement was postponed until July at least. Ahold, in contradiction with this above promise, responded to questions of AT5 about the reveal that “it was only in an explorative phase”.

The activist group Behoud Lutkemeer started protesting the plans already in 2000. Last Friday at 16:30 they symbolically announced the name of Ahold in front of the municipality building. The municipality and Ahold were requested to demonstrate “advanced insight, and act to the changing circumstances of climate emergency”. Afterward over a hundred activists continued to the nearest Albert Heijn, where they demonstrated in front and inside of the store. A follow-up action has been announced for next week Friday, this time at the headquarters of Ahold in Zaandam. “We will continue until Ahold got the message; AH has to go away”.

haal een stapel flyers en deel deze uit bij een Albert Heijn vestiging

Meehelpen?

Doneer voor de Lutkemeer De campagne en de juridische procedures kosten geld. Ook een steentje bijdragen? Doneer voor de Lutkemeer!

NL94 INGB 0007 2294 84 tnv Het Luchtkasteel ovv Behoud Lutkemeer

Geef je op voor alarmlijst Als er gedreigd wordt met zandwagens en acute actie nodig is: geef je op voor de alarmlijst. mail je telefoonummer naar info@behoudlutkemeer.nl

bijenstichting.nl/savebeesandfarmers/

Deze nieuwsbrief wordt onregelmatig verstuurd door Behoud Lutkemeer. Om ons te volgen kun je ook kijken op facebook, twitter of de website (rss-feed).

Vertel het door! Via de website kunnen mensen zich aanmelden voor de nieuwsbrief.

Veel gestelde vragen over het verzet in de Lutkemeerpolder

e

ANF | Kurds urge France to lift the “state secret” on Paris killings

The Democratic Kurdish Council of France (CDK-F) said that the French authorities have yet not removed the “state secret” on the information possessed by French intelligence services.

On January 9, 2013, in Paris, PKK founding member Sakine Cansız (Sara), KNK Paris Representative Fidan Doğan (Rojbin) and Kurdish youth movement member Leyla Şaylemez (Ronahi) were killed by three bullets each in their heads.

While the investigation revealed that the triple murder was organized by the Turkish intelligence agency, the French authorities have refused to share the information with the prosecutor who conducted the investigation on the grounds that it was a state secret.

“This refusal has a huge impact on the progress of the investigation and ensures that these terrorist crimes committed by the Turkish intelligence service (MIT) on French soil go unpunished,” CDK-F said. “Not lifting the state secret will be a serious denial of justice by the French authorities.”

CDK-F called for a demonstration at ‘28 Place Vendôme’ near the Ministry of Justice on Wednesday, 24 March, to demand the removal of state secret designation and ending impunity.

We starten een bevrijd Navalny campagne

(Een telegrambericht Vertaald met Google translate )

We lanceren een campagne om Alexei Navalny te bevrijden. Onze onmiddellijke taak is een volledig Russische bijeenkomst dit voorjaar. Een fundamenteel andere bijeenkomst – waarvan iedereen weet en die Poetin niet zal kunnen verspreiden. We zien dat volgens peilingen tientallen miljoenen mensen protestacties goedkeuren, maar als ze spontaan plaatsvinden, heeft niet iedereen de tijd om erachter te komen, niet iedereen kan komen, en velen zijn gewoon bang. Daarom zullen we het deze keer anders doen. We stellen nu geen specifieke datum vast. De eerste stap in onze campagne is om het hele land over de bijeenkomst te vertellen. Samen moeten we ons bezighouden met informatie en voorbereiding, en we zullen de datum bepalen waarop het aantal deelnemers minstens 500 duizend mensen bereikt. Op de site free.navalny.com/ hebben we een kaart gelanceerd. Als je denkt dat Alexei Navalny onmiddellijk moet worden vrijgelaten en klaar bent om dit op straat te eisen, maak dan een einde aan de stad waar je woont. De kaart zal gevuld zijn met stippen en iedereen die zijn eigen kaart plaatst, weet dat hij niet de enige is. Dat gelijkgestemde mensen naast hem wonen – op dezelfde binnenplaats, in dezelfde straat. En als er genoeg van ons zijn, zullen we in een vreedzame processie door de straten van alle Russische steden marcheren. Wees niet bang. Registreren. Doe mee met onze campagne. Rusland zal blij zijn.

the white rider

(Het leuke van … is weten op reis te zijn